After the War

[Page 358]

|

|

At a celebration of the Ichud [Unification] Zionist organisation in Częstochowa, in February 1948

Sitting from the right: the Lewkowicz family, M. Rozencwajg, Sz. Norenberg, D. Koniecpoler z”l, Mrs Zandsztajn, Mrs Winer, Dressler

Standing from the right: Altman, Pacanowski, Mrs Dressler, Rozyner, Mrs Koniecpoler, Sz. Altman, Mrs Rozencwajg, Zandsztajn, Sz. Granach |

[Pages 361-380]

After the War

On 1st April 1945, the first post–War Kehilla was established in Częstochowa.

According to what Mr Landsman tells us, the Board of Management of the Kehilla, which was headed by Mr Noach Edelist, numbered eleven people. By its side Mr J. Wajtler [sic; Wajsler] served as rabbi. He had been saved from the hands of the Nazis by hiding in the city's “Aryan side”. There was also a ritual slaughterer, who continued in the footsteps of his father, Mojsze Shoichet, who had come to Częstochowa from Kłobuck, near the outbreak of the War.

|

|

The Board of the Czestochowa Jewish Community Council [Kehilla] in the years 1945-1946

Seated (R-L): Adv.Hansfeld, L.Brener, I.Goldberg, D.Koniecpol z”l, Z Wekstein

Standing (R-L): M.Lederman, Brzezinski, Ch.Henholtz, L.Baum, L.Jurista, [?], Grinstein |

Once it had been organised, the Kehilla began to wide operate in the various areas of life and, particularly, in the religious area. The local mikvah was renovated [and] a kosher soup kitchen was set up, which provided warm meals for those in need – people who had recently been released from the camps, who were with faltering feet taking their first steps and who required aid and support. The synagogue, too, was renovated and repaired and the first prayer–groups began gathering there to worship. There, the rabbi also held wedding ceremonies for the first young couples after the Holocaust.

Although this period was characterised by migrations and wanderings of populations, with Jews coming and going, the Kehilla continued operating, with changes of management. Among other things, aid was organised for those returning from Russia and were settling in Częstochowa. A cheder was established, in which twenty–five boys and girls studied prayers, Hebrew, [etc.]. Public celebrations and parties were held and more.

In 1948, the leadership of the management changed again, when Mr Rozencwajg left and was replaced by Mr Szaje Granek z”l.

To the Ancestral Tomb

Anyone who has had the opportunity to be in Częstochowa after the War, knows that the vast majority of the city has remained standing. The same buildings, the same streets and yet, it is changed beyond recognition.

This is how the renowned public figure Rafail Federman, who in 1962 visited in Europe – Sweden, Austria, Switzerland, France and Poland – described this change:

I walked about in Częstochowa, the city of my birth, in its such familiar streets, but I felt as if I was wandering in an alien and strange world. Terror and fear seized me. My heart beat strongly! I did not come across even one Jew, one face! Everything around me was so strange.

As, with teary eyes, he approached the same house where he had lived for many years, he met the quizzical eyes of a Polish woman, who asked him, “What are you looking for here?”

“I used to live here and I wanted to see how my old house looked”, Mr Federman murmured with acute embarrassment, while the woman glared back hatefully, and turned her back on him.

Depressed and dispirited, he continued walking along the city's streets, as he called to mind the city as it had been “before the flood”, with its 35,000 Jews, institutions, yeshivas, study–halls, synagogues, cultural clubs, schools, organisations, political parties and the ebullient and fruitful life of the House of Israel!

He crossed the Nowy Rynek (New Market) – that same centre of Jewish shops and businesses, which had been turned into a square – a lawn.

And then yet another a twinge in the heart – on the site where the historical Old Synagogue had once stood on ul. Nadrzeczna, not a remnant nor a trace had been left. The ground had been levelled.

Another synagogue, the famous “Synagoga” (on ul. Wały Street), had been partly destroyed by the Nazis, then renovated and turned into the House of Culture of the local branch of the Communist Party.

After straying and wandering about the city's streets, our acquaintance Mr Federman met his landsman from New York, who also happened to be on a visit. As they reminisced about bygone days, he heard from him that, at the moment, there were 200 Jews living in Częstochowa – the majority were not locals and no one knew one another.

There was some Kehilla activity in the building that had once served as the New Mikvah on ul. Spadek, which boiled down to keeping Kashrus and the religious burial laws.

On ul. Jasnogórska, at the former palace of the textile mogul Zygmunt Markowicz, there was now some sort of cultural club, which was a branch of the Cultural Union in Warsaw. [ed: the TSKŻ – the Social–Cultural Association of Jews in Poland]

In this club, lectures or concerts were held from time to time for the handful of Jews living in the locality. Sometimes, the children of Jews came there to learn songs in Yiddish – and that was all.

At the end of his visit, Mr Federman turned to the Jewish cemetery, to the ancestral tomb and, here too, he found devastation and ruin. The majority of the ancient tombstones had been damaged, whilst the marble tombstones had been robbed and defiled in various manners. Weeds had grown wildly all around and the “hand of the Destroyer” was evident everywhere.

This picture of real–world destruction and termination blended with the devastation inside the heart and caused the Cup of Sorrow to overflow.

Every Stone was a Tombstone

Mr Ezriel Ben Moshe tells of his impressions from his visit to Częstochowa, immediately following the War:

When I left Częstochowa, the city in which I was born and brought up in, to emigrate to the Land of Israel, in my heart, I harboured the hope that, one day, I would be able to come to the city of my birth for a visit, to see my parents, relatives and friends. To my sorrow, this visit took place under quite mournful circumstances. I arrived in Częstochowa in December 1945, a few months after the Second World War had ended. At the time, I was still serving as a sergeant in the British army and I came to the city together with a group of Jewish soldiers, who were visiting Poland for the first time.

I shall never forget the mixed feelings of joy and sorrow which I experienced. The city's general appearance was very depressing. Obviously, it was not the kind of visit of which I had dreamed for all those years.

In place of the city's lively and active Kehilla, I found a small handful of Jews, individual Holocaust survivors, whom Destiny had spared, former inmates of forced labour and death camps, who had miraculously been saved. They could not believe their eyes that, indeed, before them stood their [own] landsman and that he was a soldier in the army of the Allied Forces, which had fought for their liberation.

The meetings with these Jews were heart–rending, when you heard their shocking accounts of how they had been saved and how they had managed to stay alive. They developed a great closeness with me, in their search for the fraternal bond they had been missing for such a long time. They asked about their relatives in the Land of Israel and sought advice regarding as to how to extricate themselves from the terrible place, which reminded them of the torments of hell. They were willing to put their lives at risk and to steal across the borders illegally, if only to make it to the Land of Israel.

I told the Holocaust survivors about Jewish settlement in the Land [of Israel], which was fighting for them – for free immigration and the opening of its gates to every Jew wishing to return to his homeland.

I made a tour of the city, looking for the streets which I knew well and in which Jews had once lived. Sadly, I found no trace of them. Instead, I saw ruins and piles of debris. This aroused in me a bitter disappointment and depressed me to the ground. After much vacillation, on the third day of my visit to Częstochowa, I decided to visit the flat where my parents had once lived. The building was still standing and, in the flat. lived an acquaintance, a Christian. I found myself at once leaping up the stairs but, as I approached the apartment, I felt my heart shrink inside me and, in my throat, I sensed that I was choking. Very speedily, I went down the stairs. I began running and distancing myself from that place. I felt as if every stone upon which I tread was a tombstone – that of my parents, my kinsmen and my loved ones. I continued running until the place had disappeared from my view. Without parting with my acquaintances, my feet carried me to the terminal. I left the location on the first train, fleeing for dear life.

The experience had turned into a horrible nightmare. From afar, I could still see Częstochowa, with its buildings and streets – only without the Jews of Częstochowa. The more the train distanced itself from the city, the more my surety grew that the Jewish community would never again arise in it. And looking upon the destruction of Częstochowa Jewry, my lips murmured, “Yisgadal V'yiskadash[1]…”

Ghosts on a Selichos[2] Night

And this is how Mr Szaja Landau (now a resident of Ramat–Gan and one of the directors of the “Amidar” company) describes Częstochowa following liberation. He visited there in 1958.

The wide entrance to the New Synagogue on ulica Garibaldiego had been decorated with the verse “Open ye the gates, that the righteous nation which keepeth the truth may enter in”. [Isaiah 26:2] The burning of the synagogue at the time of the invasion had not destroyed this verse and it remained on the wall, even after the War. The building was renovated and had become a concert hall, and I do not know if they left the script, which could be seen from a distance. But one thing is certain – the righteous nation which keepeth the truth shall no longer pass through its gates.

Scant shadows still haunt the mounds of ruins, unable to depart from them and, with their disappearance, the last memory of the life of Jews there will also disappear.

I perceived those shadows early one morning in Elul 5719 (August 1958), when we gathered for the first Selichos prayer. In my mind's eye, I saw before me the special preparedness which characterised the Jewish street nearing the High Holidays and, here I stood, on the brink of the wide–open abyss. All the sacred awe, which had once pervaded the night of Selichos, had given way to the depressing atmosphere of “ghosts”.

Indeed, the sadness of the prayer of those solitary individuals expressed more a lament for a terrible and dreadful past, than an appeal and an aspiration for the future.

|

|

| Board of Management of the Jewish Religious Kehilla, Częstochowa 1945 |

Remember What Amalek did Unto Thee [Deuteronomy 25:17]

When a handful of Holocaust survivors, from amongst the Jews of Częstochowa, had only begun to return to the city of their birth after the War, they at once set their minds to doing anything they could, in order to pick up the trail of the mass–murderers and to avenge their murdered brethren.

In fact, thanks to these brands[3] who were plucked out of the Nazi hellfire, the authorities were able to apprehend a few of these mass–murderers.

The Rozencwajg brothers knew someone in Breslau (Wrocław) named Kessler, who had participated in the liquidation of the “Small Ghetto”. He was brought to Częstochowa in 1946 and was put on trial. The prosecution accused him of murdering more than 300 people – among them women and children. But he only confessed to twenty–three acts of homicide and claimed, in his defence, that he had “just followed orders”. Kessler was sentenced to death and was hanged in Częstochowa.

At that same period, an officer of the local police force (the Schutzpolizei) in Częstochowa named Schmidt was detained in Germany. He was one of the organisers of the robbing of Jewish possessions, who also did not refrain from actively participating in the murder of Jews and Poles.

Very sadly, up to the beginning of his trial in 1947, no more than two Jewish witnesses were found, whereas his Polish defence lawyer presented twenty–three Polish witnesses – restaurant owners, butchers, people of the underworld, prostitutes and such – who testified in his favour. A pogrom–like atmosphere even prevailed in the courtroom and it became necessary for the police to intervene. In those days, the landsman Mr Horowicz, who had arrived from Italy, happened to come to Częstochowa. This man had been inside the ghetto during the Holocaust and, with his own eyes, had seen the accused shoot a young Jewish woman in the Stary Rynek (Old Market). Shortly after his arrival in town, he conveyed the details of this gruesome murder in court. Schmidt was sentenced to death and was hanged in Częstochowa.

In that same period, two other trials were conducted against two foremen at HASAG – Heusner and Fasold [?]. The former was sentenced to penal servitude for life for the murder of a Jewish woman and the latter, to ten years' incarceration for torturing Jewish forced labourers who had worked under him.

In 1948, Mr Bromberg was able to track down the construction manager at HASAG, who was known for his cruel murders. His surname was Oppeln, but he was best known by the nickname Hämmerl (hammer, diminutive form), which he gained through his sadistic inclination to hit victims, being transported to be exterminated, on the head with a hammer. He, too, was sentenced to death.

|

|

| The war criminal Kessler is sentenced to death in 1947 |

In this field of “remembering and forgetting nothing”, much was accomplished by Mr Jakób Bencelowicz who, in 1957, travelled from Israel to the German city of Hanau, to testify in the trial against the S.S. officer Willi Unkelbach, who had murdered many Jews. On this opportunity, he questioned Unkelbach regarding the whereabouts of Degenhardt – the S.S. captain and commander of the Schutzpolizei, who was in charge of the Częstochowa ghetto in the years 1942–1943, in the course of which 42,000 Jews were murdered. But Unkelbach revealed no details about the “Devil from Częstochowa”. The issue gave no peace to the Tel–Aviv carpentry workshop owner

and he persisted in his efforts until, after a time, Dr Erwin Shilo, the manager of the institution for the search of Nazi criminals in Ludwigsburg, notified him that Degenhardt's trail had been found and, at the start of 1966, his trial began. Together with him, two other members of the S.S. were charged – Kurt Jéricho and Otto [Alfred] Löbel.

In preparation for Jéricho's trial, in 1966, the German court turned to Israel to interrogate Mr Dawid Koniecpoler who, due to his frail health, was unable to travel to Germany.

In the testimony which he delivered at the magistrates' court in Tel–Aviv, before Israeli Justice of the Peace Dr Israel Ostrer and German judges Bodo Feilke [?], Dietrich Dreimel and Joachim Kötz [?], as well as in the presence of several Częstochowa landsleit, Holocaust survivors, Mr Koniecpoler recounted how Jéricho had murdered a Jewish woman before his very eyes:

Together with the tailor Szmul Katz and escorted by the Jewish constable Goldsztajn, we walked along ulica Wały until we reached ulica Krótk, which was deserted. Suddenly, we saw how a German police officer had dragged a woman from the gate of the school, threw her down onto the snow, drew his pistol and shot her.

This cruel murder had been perpetrated some two metres away from him and, upon now remembering the tragic incident, twenty–two years later, he was still moved to the core of his soul and tears choked his throat.

Mr Koniecpoler continued:

Considering that we were required to keep on walking on, we were unable to see what happened after the shots. The face of the murdering police officer was unknown to me, but I learned from the Jewish constable that his name was Jéricho. Several days later, this same man came to the workshop where I was working and, there, I recognised him at once.”

In answer to a question from one of the judges, Mr Koniecpoler answered that, on their way back, they passed near the scene of the murder, but the body was no longer there. They only saw a puddle of blood in the depression in the snow on the spot where the woman had lain.

Of these two criminals, Jéricho was the first in line and he has [now] already been sentenced to life in prison.

Another trial, which took place thanks to the vigorous efforts of a Częstochowa landsman, Mr Gelbhauer, was conducted against the Schutzpolizei officer named Schlosser.

Following a lengthy legal process, during which the defence attempted to acquit the criminal with various ploys, it did not succeed and so, in 1963, he was sentenced to life in prison. The defence has appealed against this conviction and Schlosser is [yet] to stand on trial for a fourth time.

In Front of the Monument to the Jews of Częstochowa

In 1963, an Israeli delegation visited Poland for the twentieth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Following the ceremony, they conducted tours of the extermination camps which the Germans had established on Polish soil, among them Treblinka, where the majority of Częstochowa Jewry had been annihilated. Among the members of the delegation was Maks Brum, who was born in Częstochowa. He summarised his impressions:

The camp at Treblinka is conspicuous for its lack of any building or structure to bear testimony to the acts of murder which the Nazis perpetrated here for years. In Auschwitz, Majdanek and other places of extermination, barracks, gas–chambers [and] furnaces have remained. Museums have been set up inside these structures, in which one can learn about the destruction and the torturing of the bodies and souls of the hundreds, thousands and myriads of our brothers. But, in Treblinka, not one structure has remained – there, only stones remain, scattered throughout the large area. Each stone serves as the tombstone for an anonymous victim. The camp resembles a gigantic graveyard.

On many stones, there are inscribed the names of cities and towns from which the Germans had brought their victims, from Poland and other lands.

With their characteristic efficiency, the Germans sent the transports off to Treblinka. They did not only operate with precision, but also with speed because, in other locations, they were already preparing Jews for the empty carriages.

Here, in Treblinka, besides a handful of prisoners who were needed for labour, all went on their last way to the “extermination facilities”.

I stood all alone in front of the monument symbolising the annihilation of my city Częstochowa. In this place were my three sisters with their children. Here, my family was murdered. Here, in this place, most of the Jews of Częstochowa were murdered.

|

|

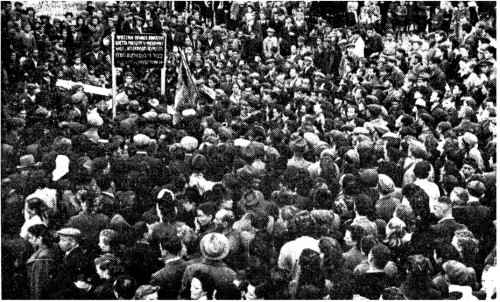

| A memorial procession on the anniversary of the murder of the Częstochowa martyrs in the Rynek |

|

|

| Memorial service for the victims of the Nazis after the Holocaust, with the participation of the Polish Army's Chief Rabbi, Dr Kahana |

|

|

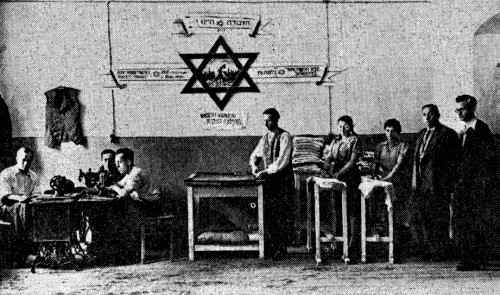

| A religious school after the War |

|

|

| Częstochowa, 1945. A memorial service commemorating the Jews who fell at the hands of the German murderers |

Five Years After the Liquidation of the Ghetto

As recounted by Mr Rozencwajg, in June 1948, all Holocaust survivors from Częstochowa and also from other places, gathered at the cemetery on the fifth anniversary of the liquidation of the ghetto, in order to commemorate the twenty–five of the city's martyrs, who were murdered in the market square on ulica Warszawska. Twenty–five candles were lit – psalms and Kaddish were said. A delegation from the Jewish Council (which, as is known, was under control of the Communists and the Bund) also appeared, with bunches of red flowers and bared heads, for the sake of three Poles who formed part of the delegation.

Zionist Activity

With the liberation of Częstochowa on 17th January 1945, about 3,000 Jews, who had been released from the camps remained. But a considerable number of them dispersed, each going back to his own pre–Holocaust place of habitation. Afterwards, the townspeople, who had survived, began arriving from the camps.

Needless to say, these were broken people, silhouettes, ruined and broken spirits. Then, a committee was organised which, at once, set about its primary mission – to extend social aid to those survivors who had begun to gather. Several months later, Mr Hillel Seidel (now a member of the [Israeli] Independent Liberals party's central committee) came to Częstochowa from Lublin and notified Mr Koniecpoler that a general Zionist party had been created in Lublin under the name “Ichud” [Unity], which encompassed all the Zionist groups and that branches had begun to also organise in other localities, in order to revive Zionist activity. Shortly afterwards, Mr Ben–Tov (nowadays, a lawyer in Tel–Aviv) visited the city and, together with local activists, set up a kibbutz called Ichud.

During that same period, the coordinators of the Zionist parties resumed their activities and instructed the organisational branches in their first steps. Among the local activists, who harnessed themselves to action were. Chaim Birnholc, Izaak Szajn, Dawid Koniecpoler, Szlojme Bromberg, Adv. Bratman, R. Szajn, Rajzman, Szmulewicz [and] Ch. Szymonowicz. At a later stage, two other kibbutzim were founded – of the religious current and of Poalei Zion (Right).

|

|

| The first Zionist Council after the Holocaust

In the photo, among others, are Rozencwajg, Granek, Zylberberg, Waga, Laks, and others |

In relation to this, it should be noted that the main activity of the Zionist organisations to their different currents was then concentrated towards training the remaining survivors to emigrate to the Land [of Israel]. Mr Szymonowicz recounts a characteristic episode from those days:

At the same time that Zionist organisations were making efforts to prepare Jews for emigration, the Communists were haranguing the Jews to stay in Poland, “to build a new life in Socialist Poland.” On ulica Jasnogórska, they established an institution for children – orphans who had been hidden with Christian families during the Holocaust.

The children stayed inside the institution during the entire course of the week and they were only allowed to go out freely on Sundays. It was on one such occasion that they found out about the kibbutz on ul. Garibaldiego 28 and they – especially the older ones among them – began to visit there. At this point, the decision was made to do something to rescue them from captivity in that institution and the operation actually met with success. Quite secretly, they were able to smuggle out fifteen children to the city of Łódź and, afterwards. across the border. Today, they are all in Israel.

|

|

| Jakub Pat [Yiddish writer] at a Częstochowa Kehilla Council meeting in 1946 |

The Religious Union

|

|

Leaders of the “Ha'Chalutz” kibbutz in

Czestochowa after the War,

with Zalman

Shazar - now President of Israel – and

Mordechai Namir - now Mayor of Tel-Aviv

Standing on sides: M.L. Szternfeld and M. Horowicz. Sitting centre: L. Jurysta |

The “Religious Union, or “Kongregacja” [Congregation], as it was later called, was founded in the summer of 1945. The board of management, with Mr Noach Edelist at its head, represented various circles from among the Surviving Remnant.

At its initiative a synagogue, a mikvah and a soup kitchen were established. The kitchen provided 100 hot meals every day (on Shabbes, the number of those turning to this kitchen was even larger).

Over the course of time, the congregation grew with the arrival of Częstochowa Jews from all kinds of places, as well as due to the addition of other Jews, from among those returning from Russia.

In the spring of 1946, Mr Edelist left for France and he was replaced by Mr Rozencwajg, who carried out the former's duties as Chairman of the board management until April 1948.

Its scope of activities also grew in parallel and the board's composition was widened, designating departments according to the nature of the matter at hand. Mrs Sztybel (now Rozener) served as the management's secretary and the office of housekeeper[4] was officiated by Mrs Adela Rapaport (now Rozencwajg). The main source of aid was the “Joint”, which sent us money and food from its branch in Łódź. A sudden crisis ensued when the Joint stopped shipping supplies and the task was put into the hands of the Częstochowa Municipality.

Agudas Yisroel

Mr Lipman Rajcher tells us about the establishment of “Agudas Yisroel's” first branch in Częstochowa after the Holocaust:

The council that was elected began operating immediately and established a religious kibbutz under the name “Beis Yaakov” [House of Jacob], which served as a home for the girls returning from the camps. In this context, we should mention Mrs Kalmanowicz's (now in Israel) exemplary activity. She displayed great devotion and love for these girls. In Israel, too, she continues devotedly supporting these young people after their immigration.

The kibbutz, meanwhile, consistently grew and, over the course of time, a second kibbutz was set up, under the name “Ohel Sara” [Tent of Sarah]. In addition, a yeshivah was also established, with a dormitory for students next to it. Regarding “Poalei Agudas Yisroel” [Aguda's workers' movement], it should be noted that the branch was very active in organising the emigration of youth, through the kibbutzim and the rescue committee and, in doing so, wrote a magnificent page in the organisation of the public–religious life in Częstochowa after the Holocaust.

|

|

| The first place of prayer after the Holocaust, on ul. Garibaldiego |

The Keren Ha'Yesod Campaign

At the start of 1948. a fundraising campaign began for Keren Ha'Yesod. At the head of the campaign was Mojsze Rozencwajg, with Judl Zonsztajn [as] vice–chairman, Szlojme Waga as treasurer and Leon Rozencwajg as secretary.

As it turned out afterwards, during the nationwide conference that took place in Wrocław, the Częstochowa branch collected – relatively – the largest sum of this campaign.

|

|

| Members of the “Ichud” kibbutz in Częstochowa after the war receive training, pending their Aliyah |

|

|

| The renowned Zionist leader Louis Segal visits the “Ichud” kibbutz in Częstochowa in 1947 |

Translator's footnotes:

- Opening words of the Kaddish, the Mourner's Prayer. Return

- Prayers of atonement which are said daily during the month of Elul, which precedes Rosh Hashana. Return

- Sticks; reference to Zechariah 3:2 – “Is not this a brand plucked out of the fire?” Return

- Ambiguous term in the Hebrew original; in this context most likely means “overseer.” Return

[Pages 381-382]

Murders – Already After Liberation

Izaak Wiszlicki

On 17th January 1945, we were freed from the camp but, even then, there was nowhere one could go.

I entered my in–laws' building. The apartments were [all] occupied by Poles. I told them that I was the owner but, from their gazes, I saw that it would be healthier for me if I were to remove myself as quickly as possible.

It was mournful for the heart to see former Jewish homes occupied by Christians. Already, in the first days following the liberation, voices could be heard, saying, “Jews to Palestine” or “What a shame it is that you survived”.

Several weeks later, Cyna Cukerman and his wife were murdered in Częstochowa as they were walking home. Dr Szperling was also murdered, when he was in Bydgoszcz. An assault was perpetrated on Dr Dobrzynski. Bandits attempted shooting him in his dwelling, but he defended himself and managed to be saved. The following day, he fled to Katowice. Later, a few Częstochowa Jews were thrown off railway carriages.

The hatred towards us was great. We could no longer live on Polish soil, which was soaked in the seas of Jewish blood.

[Pages 381-384]

How the Banners Were Concealed

Majer Rotholc

It was the beginning of September 1939. The Germans had already occupied the city and the streets were empty of people, as no one wished to be caught and, under blows, be taken for work.

On a certain day, a few of us, members of the Left Poalei Zion, met and decided to hide the banners which were in our rooms in the Stary Rynek (Old Market).

The group consisted of Mordche Baromhercyk, Szyja Gelbard, Szlojme Szymonowicz and the writer of these lines. One by one, we went to our rooms. Once there, we took a few bricks out of the wall of a small room in the loft, packed up, in newspaper, all the banners which we could find and hid them inside a hole which we had hacked in the wall. We then quickly put the bricks back in place and then sealed, smeared and wiped off all traces.

Some years later, when I was in Lithuania at the Szawle [Šiauliai] ghetto, I often wondered about the fate of my friends and of the banners which we had concealed.

At the end of summer 1945, I was on my way home. It was already evening when I arrived in Częstochowa and I made my way straight to the Old Market. Already, from afar, I could discern that the house where we had hidden the banners was still intact. There, I found Izaak Owieczka, who told me that, of those together with whom we had hidden the banners, no one had survived.

Izaak Owieczka and I took a hammer and tools and went to the rooms in the Old Market. With the caretaker's assistance, we found the door of the locale. I found the hiding–place and we extracted the package with the banners. It contained the Jugend [Youth] flag, the Gwiazda–Sztern Sport Club's flag and two storm [demonstration?] banners. Sadly, the party–banner was not there, [because] it had not been there at the time we hid the flags.

Sometime later, when I was already in Israel, I found out that Jakób Zerubavel z”l, in Poland after the War, received the flag of the Częstochowa Jugend movement, which he ceremoniously presented to the Borochov Youth in Israel.

|

|

A Bund demonstration in Częstochowa in 1946

In the first row: Brenner, Sztajnc, and Krauze |

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Czestochowa, Poland

Czestochowa, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Jun 2020 by JH